•Twigs with alternate buds / leaves (Fig. 1)

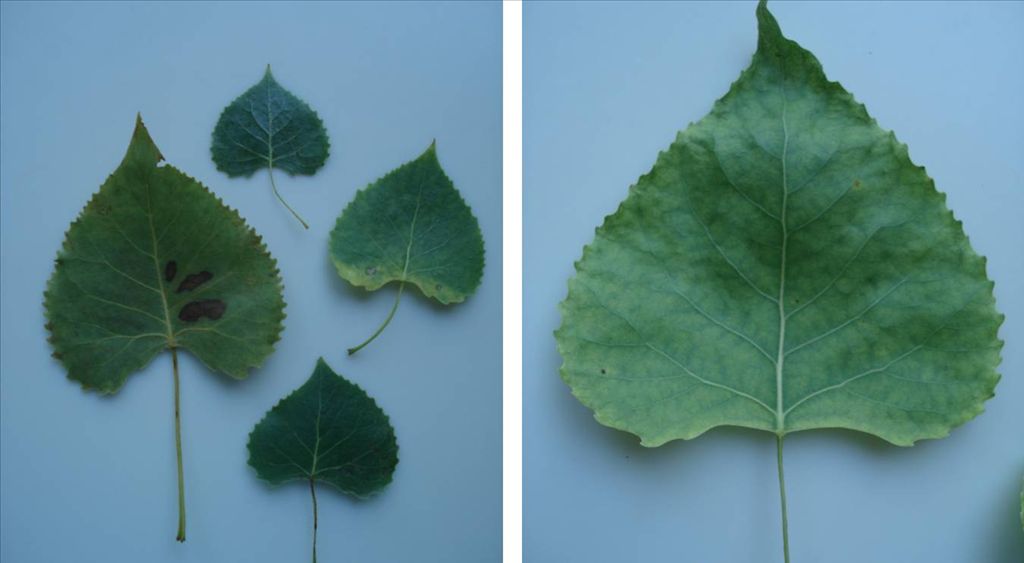

•Leaves triangular in shape, with flat or heart-shaped bottoms at the stem (petiole) (Fig. 1 and 2)

•Leaves flutter / shake in the wind due to flattened petiole (stem) (Fig. 3)

•Seeds shed in fluffy "cottony" masses in June, sometimes still attached to the catkin stalk and sometimes as individual capsules bearing a seed and tuft of white hairs (the “cotton”) (Fig. 4). Often the cottony masses are obvious for some distance from the tree. If you see even one “cotton”, you now there is a Cottonwood tree in the vicinity.

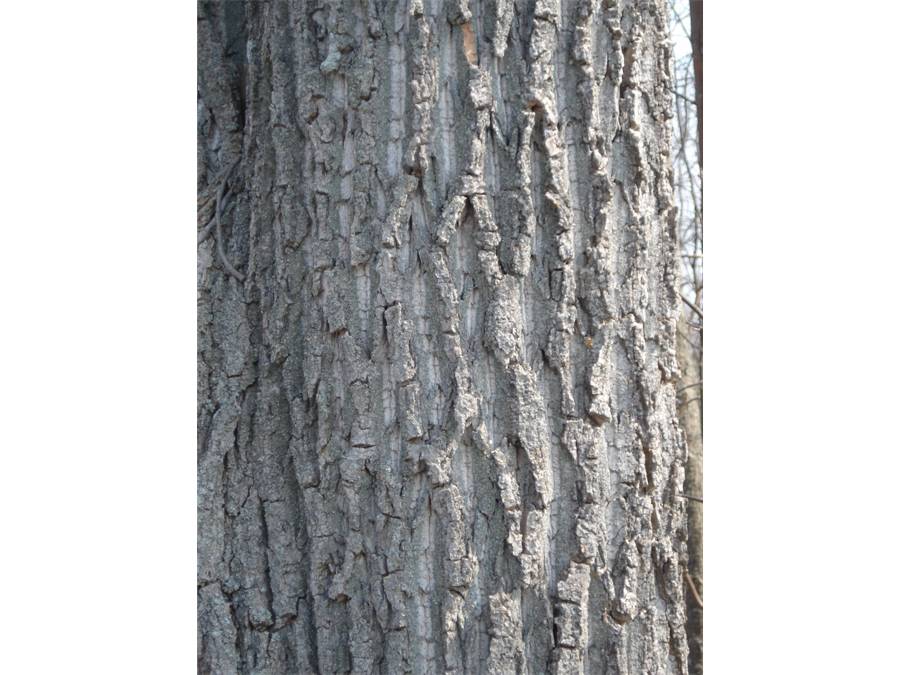

•Bark on big trees: at eye-level irregular flat-topped (Western) "mesas" with steep sides running vertically along the trunk (Fig. 5, 6, and 7)

•Historical uses: paper pulp, cheap packaging, firewood; first building material for settlers on prairie

This information is basic (not overly technical) by design and does not include total botanical information about each species (kind of tree). Rather, only distinctive features of each numbered tree in the Alabaster Bike Path-Native Tree Arboretum (ABP-NTA) are listed. Because all natural populations have variation, when considering these trees, look at as many examples of each characteristic as possible, i.e. several leaves or fruits or branching points, etc. Finally, when studying trees, the identifying “keys” are always written for a given geographic area to include ONLY ALL the trees in that area. Because our “area” is (the numbered trees in) the ABP-NTA, this information applies only to the numbered trees along the ABP-NTA; it may or may not work in neighboring areas with even a slightly different species composition. All photos and text by sczaika. Historical uses from Hough, R.B. The Wood Book. Royal Botanical Gardens.